Blue Dress. Tensions of Femininity

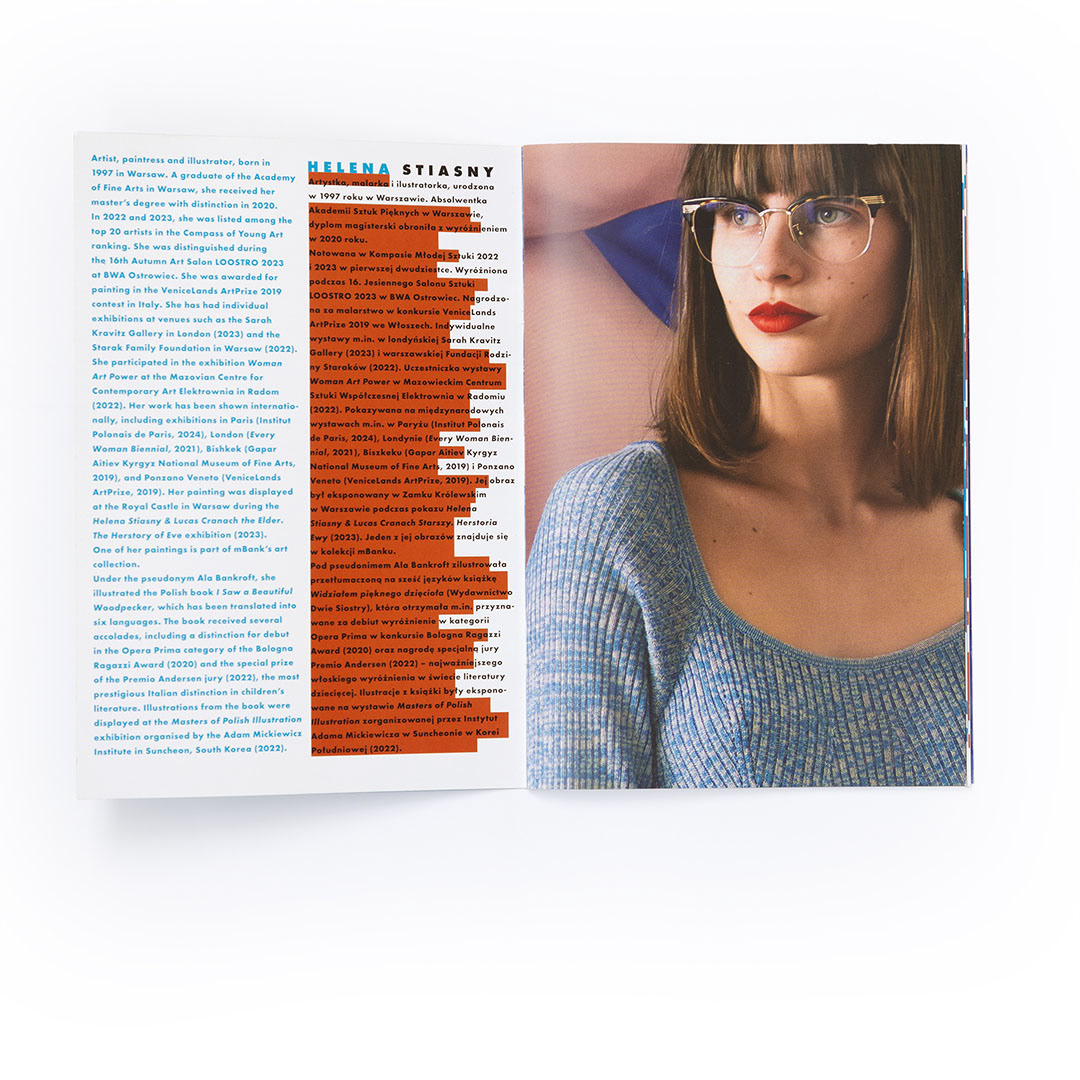

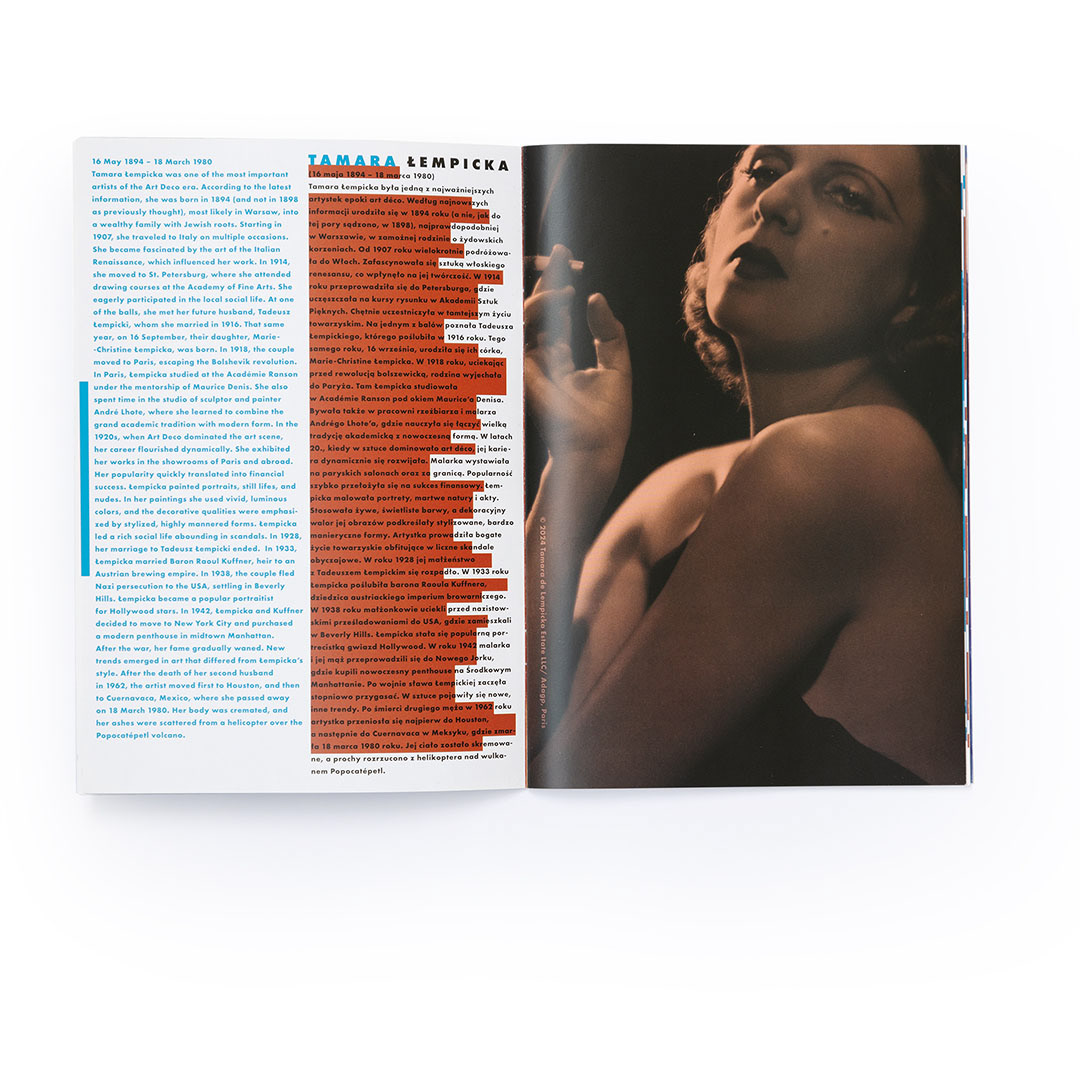

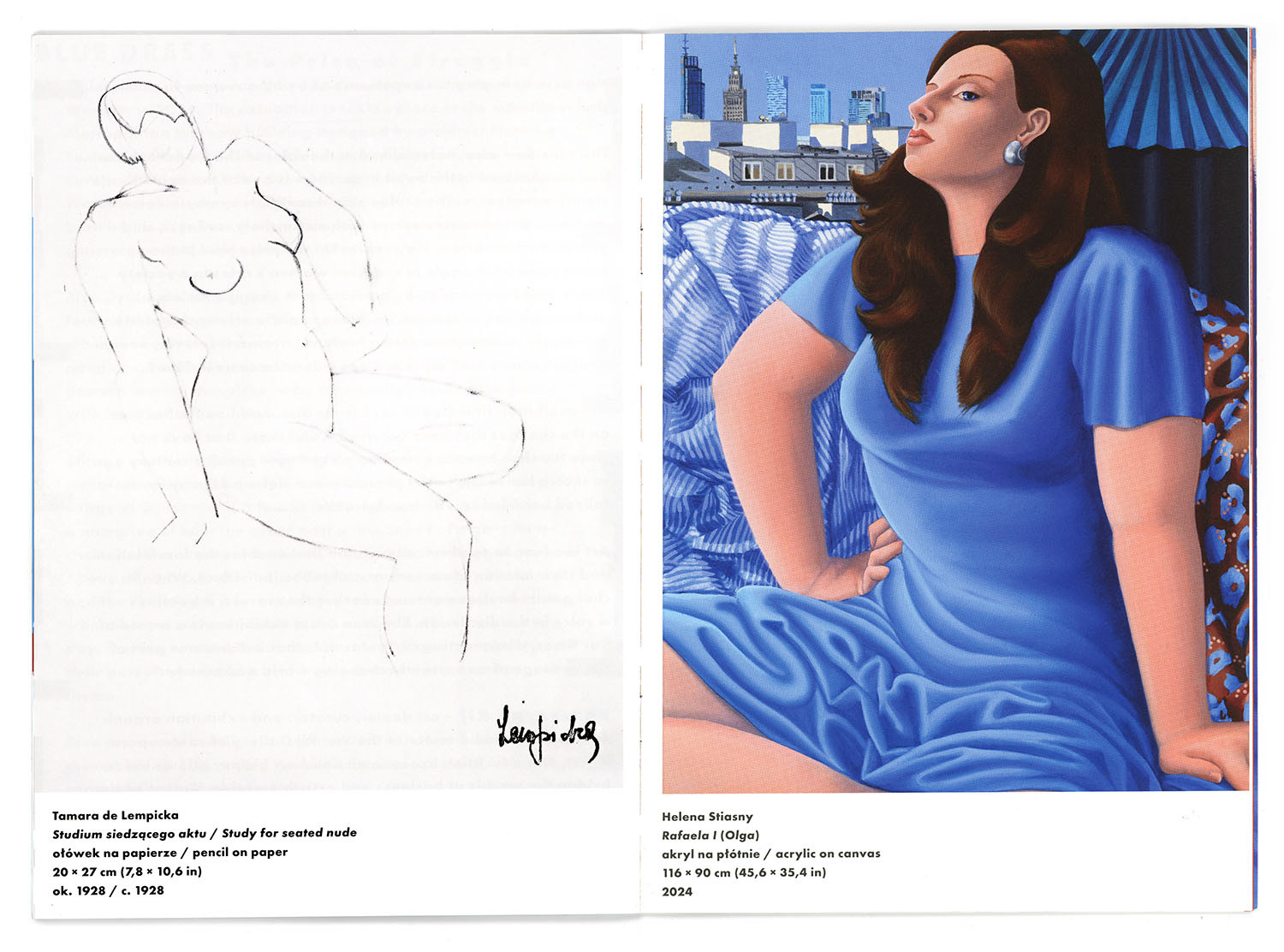

The works of Helena Stiasny are based on tensions: between the softness of fabrics and textiles and the cold gaze of the model, between the smile of a young girl and her forced, unnatural pose. Carnality here is not an end in itself but a means to anchor these tensions in the material world. Stiasny paints women who are close to her: a friend shortly after giving birth, a lawyer-friend, a drag queen. In her paintings, there is a need to break away from the internalized male view - easily found in Łempicka, with whom Stiasny enters into dialogue - and to present models from a feminist perspective, with tenderness yet free from the infantilization of femininity.

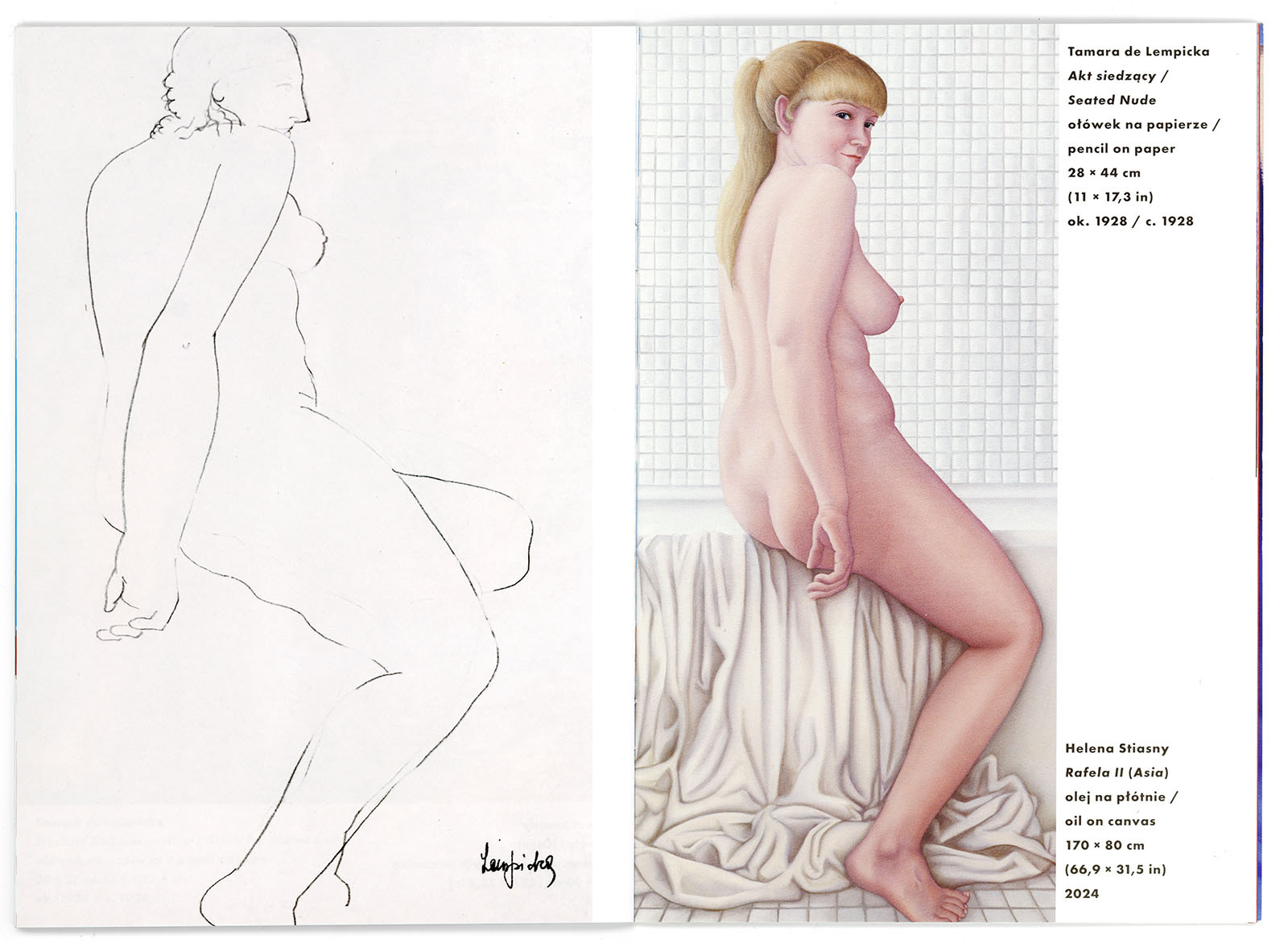

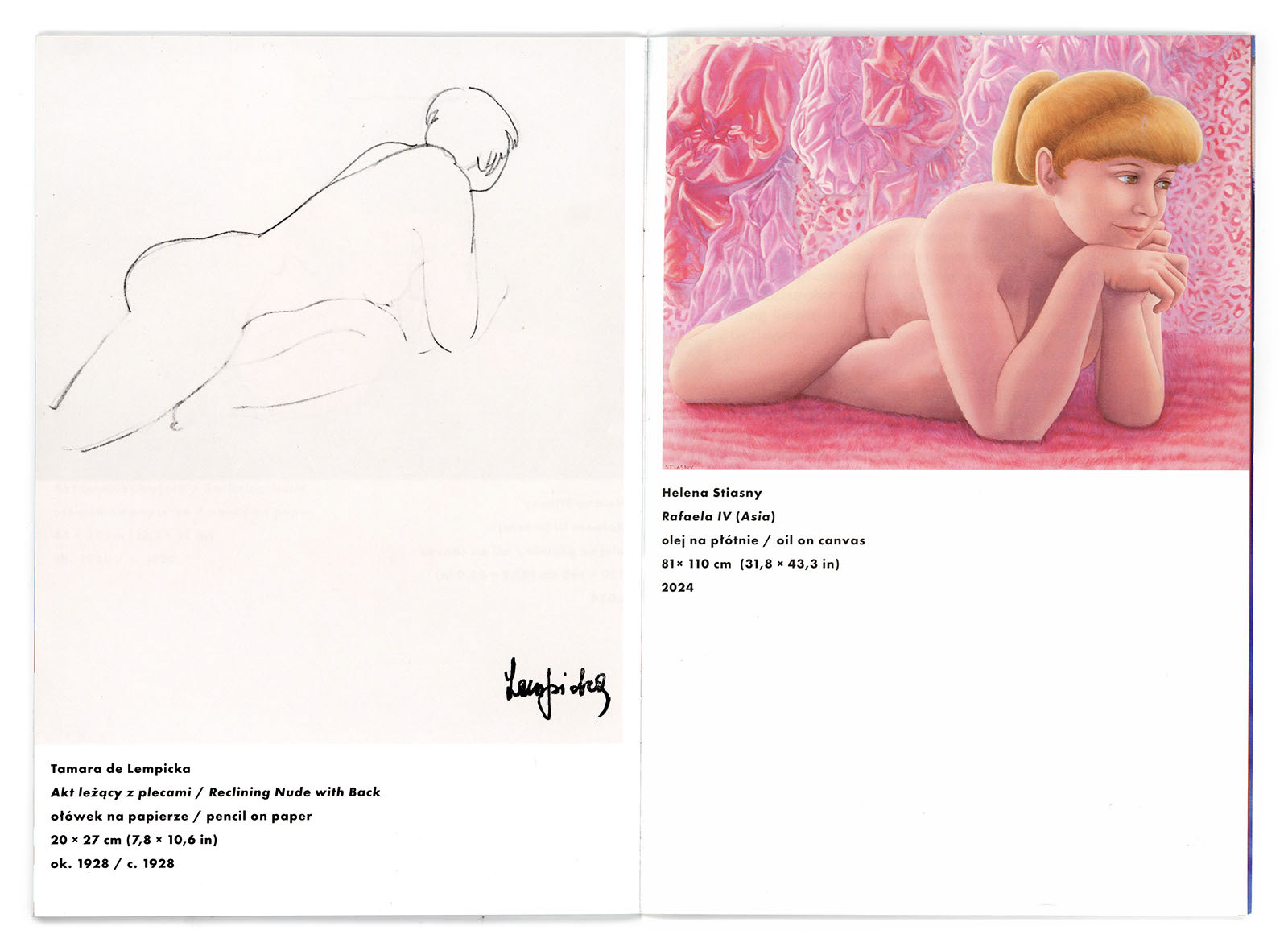

The same model appears in two of the four presented works by Helena Stiasny: a blonde with her hair tied up in a high ponytail. It is difficult to guess her age; girlishness here clashes with femininity. In one painting, the model sits astride the edge of a bathtub, gazing at the viewer; in another, she lies on a pink plush carpet.

The image of a young woman in public space is still most often constructed through objectification and sexualization, sometimes less frequently through squeezing girlish bodies into the category of cute; occasionally these two approaches combine. In Stiasny’s paintings, the nude girl is not depicted as a sexual object, yet there is still a temptation to see her as cute: in the work Rafaela IV (Asia) the softness of the fluffy pink carpet and the fabrics in the background seem to correspond with the delicacy of the model’s body.

As Sianne Ngai in Our Aesthetic Categories underscores, the category of cute eroticizes helplessness, enables sexualization, and takes away the power. When young women are portrayed as cute, they are objectified and stripped of agency.

Stiasny, however, treats her models with seriousness, drawing strength from their delicacy, showing the anxiety that is part of the experience of girlhood and femininity. The second image featuring Asia is also ambiguous.

In Rafaela II (Asia), girlishness lulls the viewer’s vigilance, but the model smiles in a cheeky, somewhat mischievous manner. In this cheeky way, Stiasny’s painting breaks the apparent gentleness traditionally attributed to girlishness and femininity. Female bodies, especially those that in any way deviate from rigid (though arbitrary and variable) standards of beauty, are still perceived as grotesque, as Mary Russo wrote in The Female Grotesque in the 1990’s. What is open, irregular, and variable, such as a pregnant or postpartum body, evokes discomfort, sometimes disgust. Stiasny’s art interestingly refers to this grotesqueness, for example, by focusing on the undulations and folds of the scenery. While Łempicka’s drawings primarily present the outline of figures, female silhouettes in Stiasny’s work are depicted against backgrounds of fabrics painted in exceptional detail, which serve as a kind of extension of the body—free, fluid, enveloping the model.

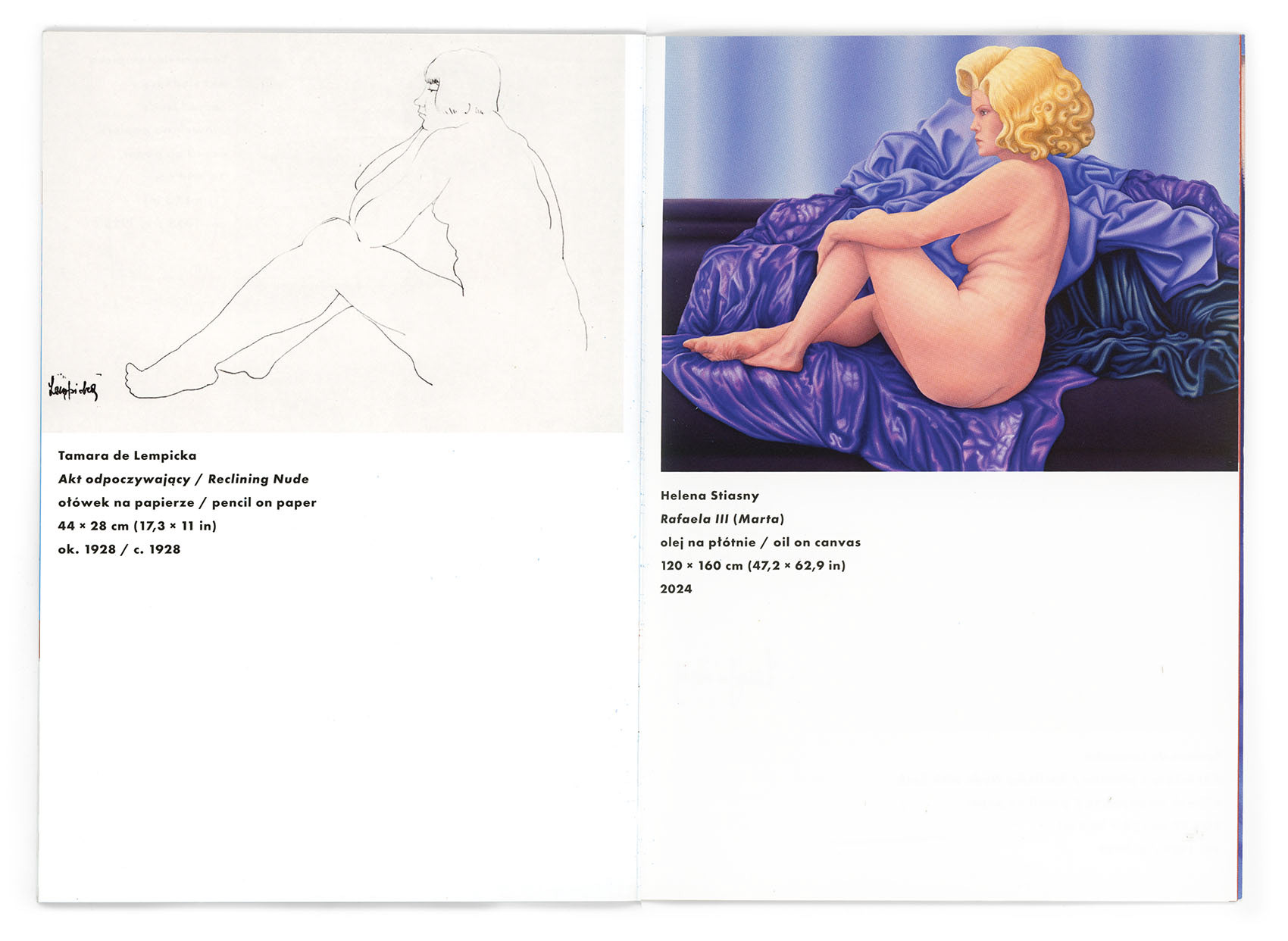

In Rafaela III (Marta), the model poses in a theatrical wig, which facilitates interpreting her character as anchored in drag and queer culture. Marta is surrounded by fabrics she uses during performances. This is also a reference to the ongoing quest to reclaim the queer aspect of Łempicka’s works—Rafaëla, the heroine of the presented sketches, was one of the painter’s lovers.

Rafaela I (Olga) is a work in which Stiasny most openly refers to Łempicka’s painting, but it also contains references to socialist representations of women, where strength was primarily physical. In Stiasny’s work, self-assurance built through posture is only part of the story: Olga’s navy-blue pleated gown in the background reveals her profession. Among the four paintings, this is the only one where the model is not nude but poses in a blue dress featured in the exhibition’s title. Stiasny does not pressure her models to pose nude—part of her feminist practice is to pay special attention to the needs and boundaries of the models.

The fabrics that Stiasny paints in such detail also visually reference the drapery present primarily in Łempicka’s early works. The rippled, flowing materials contrast with uncomfortable modernist poses in which Stiasny presents women. The dissonance between freely arranged scenery and artificial poses brings to mind the constant tension accompanying the experience of being a woman in a patriarchal reality.

Following on from Łempicka’s sketches, Stiasny requires her models to replicate Rafaela’s uncomfortable poses. In this way, she continues to ask recurring questions. How is the discourse on the female body changing? How can the subjectivity of women be conveyed in action? Art created by feminist artists is subject to continuous self-reflection—Stiasny engages in this feminist contemplation with exceptional mindfulness.

Aleksandra Kamińska is a researcher with a PhD in cultural studies and an editor. She teaches at the University of Warsaw and is a member of the Gender/Sexuality Workshop. She is a co-founder of the Girls and Queers to the Front initiative. She published in Krytyka Polityczna, The Rumpus, The Anarchist Review of Books, and the DUMA magazine and others.

English translation by Kinga Kaczor